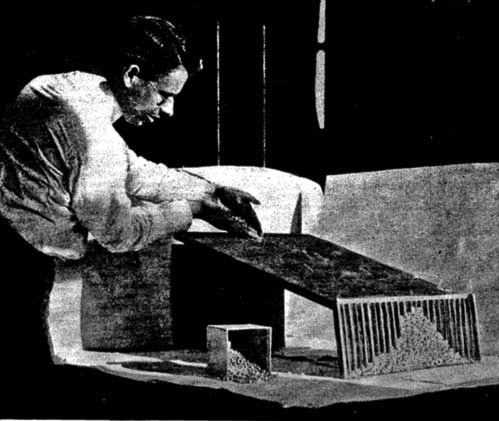

NORMAL VARIABILITY CURVE FOLLOWING LAW OF CHANCE

Fig. 13.—The above photograph (from A. F. Blakeslee), shows beans rolling down an inclined plane and accumulating in compartments at the base which are closed in front by glass. The exposure was long enough to cause the moving beans to appear as caterpillar-like objects hopping along the board. Assuming that the irregularity of shape of the beans is such that each may make jumps toward the right or toward the left, in rolling down the board, the laws of chance lead to the expectation that in very few cases will these jumps all be in the same direction, as is demonstrated by the few beans collected in the compartments at the extreme right and left. Rather the beans will tend to jump in both right and left directions, the most probable condition being that in which the beans make an equal number of jumps to the right and left, as is shown by the large number accumulated in the central compartment. If the board be tilted to one side, the curve of beans would be altered by this one-sided influence. In like fashion a series of factors—either of environment or of heredity—if acting equally in both favorable and unfavorable directions, will cause a group of men to form a similar variability curve, when classified according to their relative height.

The consequences of this for race progress are significant. Is it desired

to eliminate feeble-mindedness? Then it must be borne in mind that there is

no sharp distinction between feeble-mindedness and the normal mind. One can

not divide sheep from goats, saying "A is feeble-minded. B is normal.

C is feeble-minded. D is normal," and so on. If one took a scale of a

hundred numbers, letting 1 stand for an idiot and 100 for a genius, one would

find individuals corresponding to every single number on the scale. The only

course possible would be a somewhat arbitrary one; say to consider every individual

corresponding to a grade under seven as feeble-minded. It would have to be

recognized that those graded eight were not much better than those graded seven,

but the drawing of the line at seven would be justified on the ground that

it had to be drawn somewhere, and seven seemed to be the most satisfactory

point.

In practice of course, students of retardation test children by standardized

scales. Testing a hundred 10-year-old children, the examiner might find a number

who were able to do only those tests which are passed by a normal six-year-old

child. He might properly decide to put all who thus showed four years of retardation,

in the class of feeble-minded; and he might justifiably decide that those who

tested seven years (i.e., three years mental retardation) or less would, for

the present, be given the benefit of the doubt, and classed among the possibly

normal. Such a procedure, in dealing with intelligence, is necessary and justifiable,

but its adoption must not blind students, as it often does, to the fact that

the distinction made is an arbitrary one, and that there is no more a hard and

fast line of demarcation between imbeciles and normals than there is between "rich

men" and "poor men."